The tale of a child running away from home is a familiar story. Often it’s told with the young protagonist marching away in defiance at some perceived injustice, only to return upon the discovery that it’s a big world out there.

My own story of running away from home is a bit different. It begins with my flight from almost certain punishment, and ends when anguish turns to relief. And my lesson: fatherly love isn’t always easy to recognize, but it’s there just the same.

I was five-years old in 1963, living in a ticky-tack little box in suburban Columbus, crammed with four older siblings, two younger siblings and my parents. The house had so little room left to maneuver that dad was forced to resort to clever engineering and ingenuity to solve our space problem.

One of the contraptions he put together was a system of ropes and pulleys that lifted his model train-set up to the ceiling when it wasn’t being worked on. This cleared way for other activities to be pursued using that same basement area.

Before I was born, dad worked briefly for a railroad company, so he took his train-set hobby seriously, building model houses to scale, placing ballast on the railroad tracks, and creating greenery resembling bushes and trees from sphagnum moss.

There was a firm rule though, which all of us children knew: we had our toys and dad had his. We were not to touch the train-set when he wasn’t around.

Of course this was the source of trouble, and the reason I ran away from home one day. The model layout was too enticing. Not only did it have relay-based track switches, and lighted houses, and engines pulling stock cars in opposing directions, it also had matchbox model cars. And these were too tempting to resist. They begged to be pushed around that model fantasy land. So when no one else was around I succumbed.

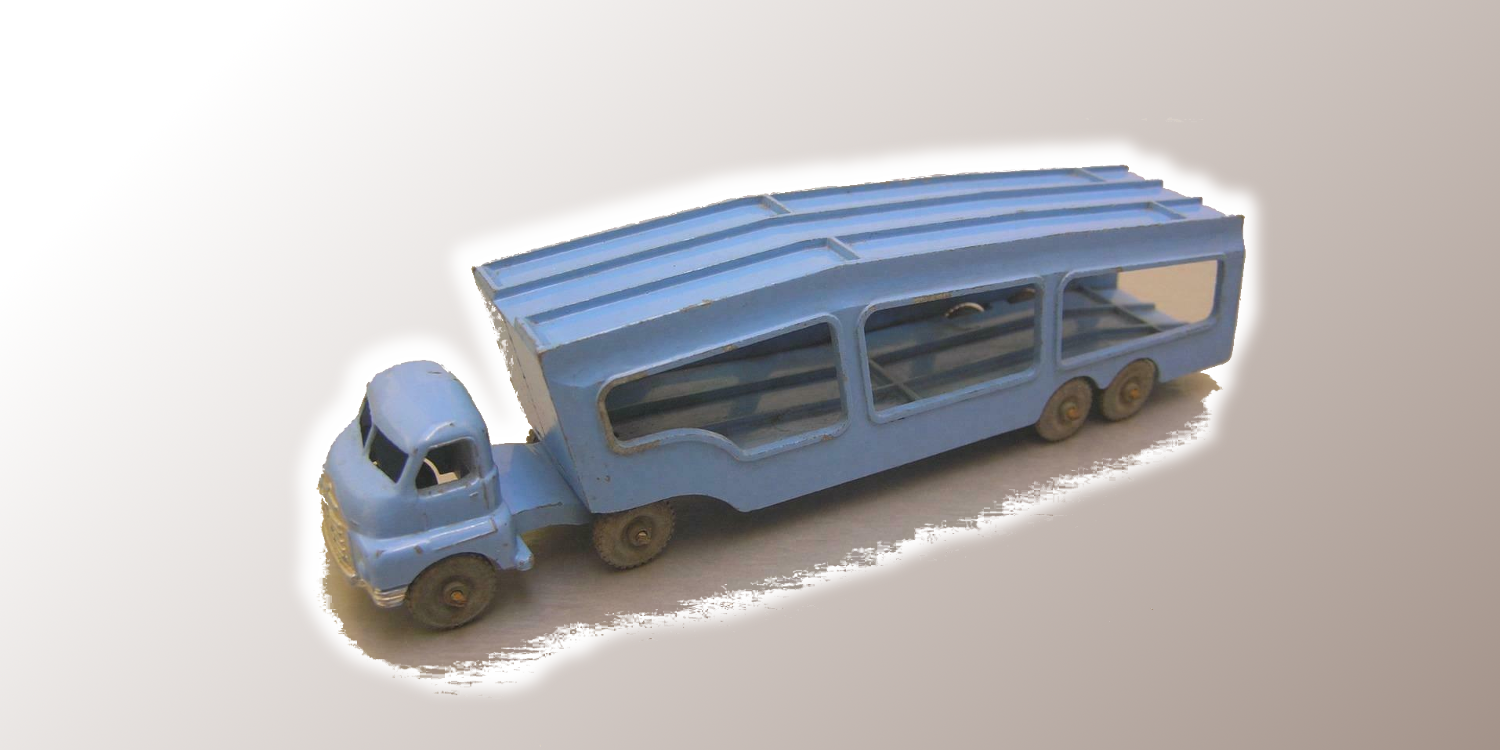

Pushing little cars around was good fun, and I was just old enough to do it without breaking anything. But one of the matchbox models stood out from the others. It was a 1957 Bedford car transporter, with a swivel-hinged front cab and a four-car hauler. Oh, pushing that around would be a delight! And even better would be loading it with cars. Well, I had some of my own toy cars so I thought it would be fair game if I tried using them instead of dad’s. One of the toys in my pocket at the time was a green army jeep, which it turned out was a different scale model from the Bedford. The jeep was a bit too big to properly fit, and so it got stuck in the carrier’s lower deck where my tiny hands couldn’t free it.

I panicked at the thought of being discovered, of having disobeyed dad’s strict rule, of mixing my dirty sandbox jeep with dad’s pristine Bedford, of possibly even scratching its brand new blue paint.

And so I ran away. Or rather, I hid myself in the basement laundry room.

Hide-and-seek was one of the games we often played in that basement, so I knew all the good places. My choice that afternoon was under the utility sink, scrunched between its drain pipe and legs, carefully hidden behind a basket of dirty clothes waiting to be washed. The laundry room was poorly lit, having just a single bare light-bulb and a half-height window which let in faint light from the outside. I was hidden in the darkest pocket of the room. I don’t recall how long I stayed there, but it was long enough to create a lasting association between that day and the odor of damp, musty laundry.

Staying hidden wasn’t hard to do. After all, when the seven of us children all played hide-and-seek it could take a while for everybody to be found. So I waited patiently. At first, nobody was looking for me. The usual commotion of family life was occurring upstairs and outside, with no one the wiser.

Eventually someone noticed that I wasn’t around, and scouts were sent to every room in the house and every corner of the back yard. One of my siblings peeked into all the usual basement hiding places, even coming close to finding me, but I was too well hidden, and the room was too dark, so I remained undetected. After that near miss, my nervous energy subsided, and I nodded off for a bit.

Meanwhile the search widened. All the neighborhood rug rats on their tricycles and skates were stopped and queried. “When was the last time anyone has seen Joe?”

Matters took a serious turn when my parents called the police. They arrived promptly, asked the usual questions, then remained on hand as the search expanded to the wider neighborhood.

I suppose it was the smell of dinner being cooked that brought me to my senses. Soon after, somebody doing another round of poking about came close enough to my hiding place that I willing revealed myself. My self-imposed asylum was over. It was time to accept my punishment.

Trembling and tears were followed by hugs and reassurances. And questions: why was I afraid and why was I hiding? I confessed to the Bedford disaster.

Dad carried me out of the darkness and over to the scene of the crime, took a quick look at it, and effortlessly freed the army jeep from its stuck position. There were more hugs and more declarations of love as I was carried upstairs, and the police were thanked, and the hubbub of the Honton tribe quieted down several decibels, and we settled into our proper seats for dinner.

I didn’t need to discover the big world just yet. I had my family.

by

by